About San Francisco

Gaspar de Portola discovered the San Francisco Bay in 1769.

Gaspar de Portola discovered the San Francisco Bay in 1769. Gold was discovered in 1848, which led to the arrival of thousands of immigrants from different parts of the world, each from a new country searching for a new life. People from Asia, Europe, from South America, Australia, or from America’s east coast settled in different parts of the city, which led to many of its most famous neighborhoods today. As early as 1854, it was recorded that “street life in San Francisco is a kaleidoscope that never rests.”

Jasper Ofarrell laid out a grid for San Francisco in 1847. Blocks north of market were uniform and had an east-west orientation. Block measurements were 150 by 100 Varas. (412 ft x 275 ft) These were then broken up into lots, often 25ft wide by 100ft deep. Flat areas were settled first, and as the city grew, the grid was extended into the hills. This use of a grid planted over San Francisco’s hilly terrain made for a unique and dramatic landscape. Entire blocks were sold for about $72, and houses were put up and fast as the population grew. Many of the earliest buildings were made of whatever materials were available and not constructed well, and because of this, the city suffered eight major fires by 1855.

The people who became rich at this time were not the gold miners themselves, but the shop owners who provided them with goods or housing. San Francisco’s elite began to gather around Rincon Hill and South Park, and this was the city’s first affluent area. Not much remains today as the area burned in the 1906 fire and Rincon Hill was razed to make room for the Bay Bridge in the 1930’s. In 1873, the Cable Car was invented by Andrew Hallidie, which changed the dynamics of the city forever. The cable car made many of the areas steeper hills accessible, and it became popular to build on hilltops, as they afforded the best view and separated the elite from the masses below them. Mansions were built on top of Nob Hill and in Pacific Heights, and everywhere that cable car tracks were laid. At the height of their popularity, there were around twenty cable car lines within city limits.

At 5:12 am on April 18th, 1906, San Franciscans were awakened by over 1 minute of violent shaking – their city was about to change forever. An estimated 8.3, had the Richter scale been invented, the earthquake was compounded by three major fires (the Chinese Laundry Fire, Domenico’s Fire, and the Ham and Egg Fire) which eventually joined into one and burned for the next three days. A huge fire started at Gough and Hayes Street burned down City Hall and the most developed portion of the city. Homes and buildings were dynamited along the wide Van Ness Avenue to contain the fire. When the fire subsided, an estimated 3000 people were dead and 250,000 were homeless.

There was a major panic that new businesses and individuals wouldn’t want to invest in the city for fear of another earthquake. The result was a massive media cover-up, assuring everyone the fire, not the earthquake was what destroyed the city. To this day it is referred to as the “Great Fire” instead of the great earthquake. The official death toll is 371. Over 500 city blocks were reduced to ash, yet by 1915; most of the city had been rebuilt as San Francisco hosted the World’s Fair. The great speed of rebuilding resulted in relaxed building and fire codes.

Buildings built in the last fifty years follow a strict code to withstand another shock. Older buildings as well as hotels are retro-fitted and placed on stabilizers. Most structures today are steel framed or constructed of reinforced concrete. However, San Francisco is largely a wooden city, and many of the remaining houses in the “old” quarter, which were outside the fire zone have never been altered. Today, the Great Earthquake and Fire is a distant memory for the city. Every year the remaining survivors meet at Lotta’s Fountain to remember those times. Most were four or five years old at the time.

During the later half of the 19th century, there were 40,000 Victorians built in San Francisco. Because of Fire, Earthquakes, poor up-keep, large tracts of subsidized housing, and generally falling out of favor, there are now between 14,000 and 18,000 left. There s a range because several have been altered so much, it is difficult to tell how they originally were. Most of the surviving Victorians today are in the central part of San Francisco. The 1906 fire destroyed almost everything East of Van Ness. (Nob Hill, Financial district, Russian Hill, etc)

There are four main eras of Victorian Architecture. The first style was known as Carpenter-Gothic. They were usually small and did not have much ornamentation. There are not many surviving examples; a good place to see them is Telegraph Hill. The 2nd style is Italianate. Their most discerning feature are slanted bay windows. These started to move out of fashion by the 1880’s, as the Stick-Eastlake style took over. These have rectangular bay windows and are generally pushed out a little farther, increasing interior space. The last style was Queen Anne, which are identified by their round turrets.

As the city was laid out in rectangular blocks, corner lots are desired and went for more money. Lots facing north and south were more expensive than “key” lots (facing east-west). Alleys were cut through blocks for smaller residences or servants quarters. Single builders would design entire blocks of row-houses, cutting costs, thus making it easier for more people to own their own home. Several implementations such as balloon framing, standardized window, door and fixture sizes, and centralized plumbing also brought prices down.

The interior of these homes is a maze of rooms, as it was popular to have a different room for every daily function. Even modest middle-class Victorians were compartmentalized into ten or more rooms, including a sewing room, butlers pantry, hallways, servants quarters, a nursery, double-parlor, or a wine cellar. Sliding doors usually divided houses into public and private areas.

San Francisco’s Victorians fell from public taste in the 1920’s and with more cars, many people moved away from the city center. This is a trend that is seen in most major U.S. cities. As the city center deteriorated, entire blocks of Victorians were razed to make room for subsidized housing developments. In the mid 1970’s, they fortunately became popular again. Many were painted with multi-colored schemes to accentuate detailing and make them look new again. (Most Victorians were one color when they were built).

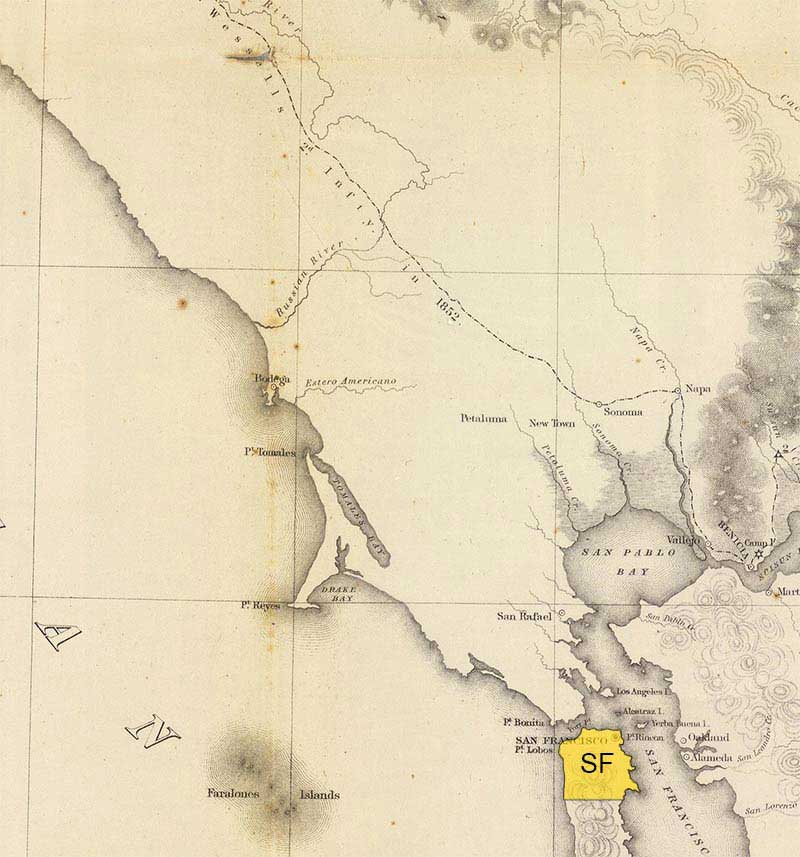

Map: David Rumsey Collection

Sandwiched between the busy financial district, bustling residential neighborhoods and the sea, stands Telegraph Hill. At approximately 20 blocks in size, it is the smallest of the 46 hills within San Francisco city limits, yet one its’ most historic. Whimsical bohemian cottages dating from the 1860’s perilously cling to the steep eastern cliff face, while the gentler sloping west side harbors a distinctly Italian feel. Residents who come to live here discover an island of tranquility; complete with overgrown foliage, quiet dead end streets and spectacular views the ever changing colors of the bay. Inspiration hovers around the summit, as past residents Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce and Armistead Maupin have all found.

The history of Telegraph Hill dates back to the gold rush. Before then, it was simply known as Punta de Loma Alta (point of high hill). In 1848, gold was discovered in California, sparking the largest gold rush in history. San Francisco grew from 1,000 inhabitants, to 25,000 full time residents in less than two years. As there was very little flat land available within the city center, miners would set up tents on the surrounding hills and camp for a few days, before heading east. The Spanish name was dropped, and the more Americanized “Prospect Hill” was adopted. After the frantic pace of gold seekers died down in the subsequent years, the hill changed names once again and became known as Billygoat Hill. Tents were replaced by temporary wooden shanties, and eventually by permanent housing.

At that time, San Francisco was so isolated that a ship was often the only link to the outside world. Since the 284 foot high peak was visible from every point in the city, a signal station was built to announce the arrival of ships to the town below. Incoming ships ending their six-month voyage would carry news, mail, family members, and catalogue ordered items. Longshoremen constructed modest homes along the hill’s eastern slope so they could be the first to run down and work unloading incoming vessels. Eventually, another signal station was built at Point Lobos on the Pacific so that the signal could be telegraphed further in advance. It is from these stations that the hill took its present name.

Sailing ships brought cargo, but needed ballast upon leaving, so the eastern and southern flanks of the hill were blasted away to produce gravel. Evidence of this blasting can still be seen at the intersection of Filbert and Sansome , as well as north of Broadway Street.

Jasper O’Farrell is credited with surveying and expanding the existing streets of San Francisco in 1847, but his grid layout seems to be abandoned at the foot of the Hill. In those early days, the only access to the homes at the crest was a countless number of stairs. Once they reached the upper plateau, residents then followed goat paths to their destination. Irish immigrants first settled this area, with Chileans taking the lower western flanks.

The 1860’s saw a new wave of immigrants: Italians, who were eager to escape the friction of Garibaldi’s unification, settled and eventually overtook the Chilean quarter. The few blocks – with narrow alleyways, espresso café’s, and house made pasta hopes reminded them of the world they had left behind. During the great earthquake and fire in 1906, these Italians were able to beat out the flames with clothes soaked with wine from their cellars. Their effort in saving a few houses was heroic, but by the time the fire had died out three days later, over 80% of Telegraph Hill lay in ruin.

Work to rebuild San Francisco began as soon as the fire was put out. Huge tracts of apartment buildings were immediately constructed to compensate for the 200,000 residents who had been left homeless. In fact, all evidence of the disaster was erased by the Pan-American Exposition nine years later.

In 1929, Lillie Hitchock Coit, one of San Francisco’s wealthiest and most eccentric personalities, left $50,000 for city beautification. The money was spent erecting a classically fluted tower bearing her name. Coit Tower stands at the site of the old signal station, and affords wonderful 360 degree views of Downtown, Russian Hill and the bay. More recently a statue of Christopher Columbus was added.

Today, the most scenic, although most physically demanding was to reach the tower is from the east via the Filbert or Greenwich steps. Residences in this steep neighborhood are only accessible by foot. Surrounded by lush tropical gardens and the sounds of parrots overhead, visitors are immediately drawn into a world away from the busy one below. About 700 residents are lucky enough to call this area home, their houses having escaped major catastrophes as well as the wreckers’ ball. They can say they live on a mountain, on the water, and in the city all at the same time.