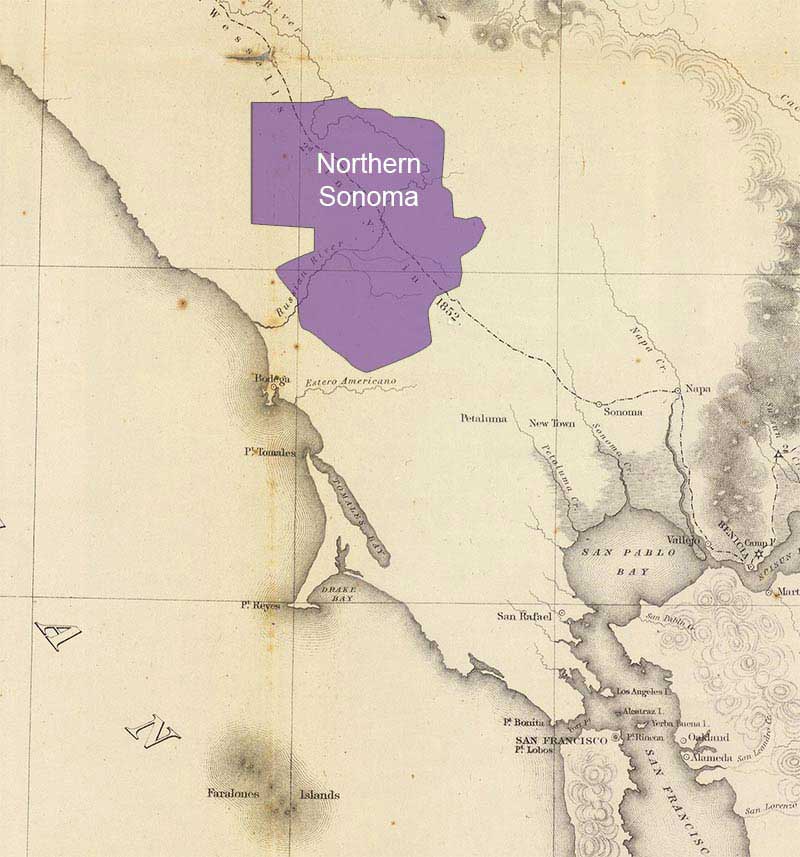

About Northern Sonoma

Sixty miles north of San Francisco

Sixty miles north of San Francisco, the Coastal Mountains extend into the sky from the violent ocean below. It is home to the tallest trees in the world, the coastal redwood. Slicing its way over this almost impassable terrain is the Russian River, where our famous Sonoma private wine tours from San Francisco show guests small, private vineyards and a variety of grapes grown in the region.

In the world of wine, several famous rivers have governed the land: the Rhine, the Loire, the Douro, the Saône. The Russian River is also included. Climates vary so much that it results in a wide-range of grapes in San Francisco: the Bordeaux varieties are grown in the inland Alexander Valley, and Rhone Varietals along “The Crucible,” while Burgundian grapes dominate “The Middle Reach.”

The Russian River dominates the northern end of the Sonoma American Viticultural Area (AVA). Sonoma was the birthplace of American fine winemaking, and although Napa Valley gained prominence during the fine wine resurgence of the 1960’s Sonoma is on the rise to dominance once again. There’s a broader range of grape varieties that can be planted in Sonoma. Sonoma’s sheer size, much of it unexplored, also attracts a lot of wine enthusiasts from San Francisco and other locations.

Russian River’s first human inhabitants were the Pomo Indians, who aptly named the river “Shabakai” meaning long snake. The Pomo fished Salmon during the winter and hunted the plentiful deer and elk. California was a wild place then, but this was soon to change. In the race to claim California, Spain established several missions running up the coast, the northernmost being San Francisco Solano about twenty-five miles distant. In an effort not to let the Spanish any farther up the coast, the Russians established Fort Ross on the mouth of the river. They hoped that California would be warmer and dryer than Alaska. They lived peacefully with the natives peoples, as it is evidenced that there were several marriages during the Russians stay, as well as several Russians who learnt the Pomo language (certainly uncharacteristic of the Spanish).

While California is certainly dryer than Alaska, the coast still gets over eighty inches (and often over 100 inches) of rain a year. The Russians tried to plant crops, but the ground never saw the sun in the summer because of the fog and hillsides came down in a series of mudslides during the winter. Moreover, during the winter months the river becomes a raging torrent, which changes course every year, destroying everything in its path. This lack of sustainability, coupled with the growing Spanish presence, caused the Russians to retreat north in 1842. A few Russians stayed and journeyed inland, but aside from that, the rivers’ name is about all that remains from that era.

The Spanish never acknowledged the Russians claim to the land. After Mexico won her independence from Spain, the new Mexican government sent Cyrus Alexander and Captain Henry Delano Fitch north to find land fit for a cattle ranch. These were the first permanent settlers and Cyrus Alexander gave his name to Alexander Valley. California changed hands once again, this time becoming part of the United States as thousands of immigrants started arriving, searching for gold. When these newcomers failed to find this elusive metal, they searched for suitable land for farming. The Russian River’s proximity to San Francisco made it a prime choice. Additionally, settlers noticed the red volcanic dirt, which has been recognized as good soil for grapes since the Roman era. A town was established a few years later by the name of Healdsburg, which became the little wine capital for the region.

Today, the main varietal grown in the Alexander Valley region is Cabernet Sauvignon. These wines tend to be softer and simpler than their Napa counterparts. Equating it to the Bordeaux region, one could say that Alexander Valley is the St. Julien of the north coast while Napa is the Pauillac. This however, has not always been the case; up until thirty years ago, Zinfandel was king. As San Francisco grew exponentially following the gold rush of 1849, large amounts of wine were needed to support the population, since it was isolated from the rest of the country. Vineyards were planted with “field blends” of more than one type of grape. The big seller was Claret, which basically meant the wine was dry, red and full-bodied. Other popular varietals of the day were Sangiovese, Mourvedre, Petite Sirah, Tempranillo, and Nebbiolo. Many of the vineyards from this time are still field blends, meaning that many Sonoma Old-Vine Zins are not actually 100% Zinfandel.

By the 1880’s, the United States was experiencing a post-civil war boom, and now that there was a railroad connecting California with the populated east coast, the demand for grapes and wine was greater than ever. Many Italians arrived at this time, and huge portions of the Russian River were settled. Italian immigrants sent home letters describing a beautiful river and countryside which reminded them of the hills of northern Italy. Everyone lived in relative prosperity until 1919, with the onset of prohibition. With alcohol now illegal, many growers went bankrupt and moved out. When prohibition ended in 1933, things were slow to start up again, as Americans leaned toward beer and spirits. During the 1960’s, there was a major shift in the wines people drank. The big gallon jugs of Claret went out of style, and were replaced with single varietal 750ml bottles.

Around this time, it was discovered that Burgundian grapes, particularly Pinot Noir, thrived in the valley. Vines were planted in the rich deposits of gravel immediately adjacent to the river, which insured excellent drainage. Cool climates allow Pinot Noir to express its delicacy and terroir, and the majority of California’s top Pinot comes from the confines of the Russian River Valley. The region has long had a Burgundian tradition of vineyard designate bottlings (one grower selling grapes to one or more wine-maker, who in turn puts the source of the fruit on the bottle).

Pinot Noir is one of the oldest grapes varieties known and has been grown for at least 2,000 years. Because of its long history, it has had more time for clones to develop. There are currently over 100 different types of this grape. Several of them were developed in the town of Dijon, France. During the early 1980’s, the word spread that these Dijon Clones existed, and several Californians went to France and came back with budwood, which could be used to grow new vineyards. Clones 5, 115, and 777 as well as Pommard clones were especially valued as they grew the best in California. The ongoing debate is whether these single clones make the best wine, or if the old selections are superior.

As Pinot Noir reflects the terroir, or conditions it was grown in, we have seen two distinct styles emerge over the past decade. One is the more muscular, darker style, which can grow in a wider set of climates. The average Brix levels (% of sugar when the grapes are picked) when making this style has risen almost 10% in the past decade in the pursuit of a richer, riper wine. The other style is more elegant and refined, approaching the Pinot houses of Burgundy. These wines are characterized by higher acidity and lower alcohol, with more delicate and mineral nuances. Often wineries in the region will make at least one of each, in an attempt to satisfy peoples’ different tastes.

It is interesting to look at is how two different wines made using grapes from the same source can taste completely different. Pinot Noir needs a long hang-time, and very moderate temperatures. If it is too hot, the resulting wine will have too much alcohol and low phelnolics (aroma and flavor compounds that give wine its complex flavors). If the weather is too cold, the wine takes on an unripe green vegetable flavor (think asparagus). One thing is certain; ten years ago American winemakers struggled with Pinot Noir, often citing that it was the most difficult grape to grow. Today, it is the most exciting and upcoming grape, with the best yet to come.

Map: David Rumsey Collection

Map: David Rumsey Collection

Sonoma was the birthplace of American fine winemaking, and although Napa gained prominence during the fine wine resurgence of the 1960’s, Sonoma is on the rise to dominance once again, due to the broader range of varietals that can be planted here. Another reason is its sheer size – larger than the State of Rhode Island – and much of it still unexplored. It is less flashy than Napa in both architecture and wine. Sonoma is a collection of small valleys, as opposed to one large valley like Napa.

The climate ranges from maritime (with some vineyards not ripening at all some years), to hot Mediterranean. From coolest to warmest they are Sonoma coast, Russian River, Carneros, Sonoma Valley, Dry Creek Valley, Alexander Valley, and then Knights Valley. Fog again is a major issue, rushing in from the Pacific through the Russian River, Petaluma Gap and Carneros, and bringing relief from the hot sun. 24 hours of fog is equal to one inch of rain, with areas on the coast recording 100 inches in some years. Storms coming off the ocean must pass through Sonoma first, often dumping the majority of their rain there before moving on to Napa. The rainy season is December through April. Soils vary from one area to another, influenced by volcanics and elevation.

Dry Creek Valley has the highest concentration of old Zinfandel vines in the world. It can be attributed to one man, Andrea Sbarboro, owner of the Italian Swiss Colony. In the 1880’s he brought in his own workforce from Italy. Once here, they would live on property and work at the winery or vineyards without pay. At the end of three years, they would receive a lump sum, and many of them would buy nearby land, planting it to Zinfandel and selling it to Swiss Colony. Over the years, many of these vineyards became prized, leading many growers to start making their own wine. That is why most wineries here are small and end in a vowel. Soils here are red clay and gravel, a mixture known as Dry Creek Conglomerate. Like Napa, the south part of the valley feels more ocean influence, while the north is warm enough to ripen Cabernet. Zinfandel is still the main variety, planted as bush vines with no irrigation. The wines have flavors of plum and bramble, and tend to have less tannin than Napa Zin. They can also be peppery, a signature that the vine is older. Lesser examples taste pruney, a sign that harvest was delayed too long. Dry Creek also produces Sauvignon Blanc and Rhone Varietals.

Russian River Valley is the largest and most varied region of Sonoma. It seems less of a valley and more of a round bowl that fills up with fog. The Russian River, with its still colder sub-AVA Green Valley benefit the most from the cooling effect of the Petaluma Gap, with fog often lingering past 11am. The most common soils are sandy and fast draining, becoming heavier as one moves north and west. There is a mix of large and small producers. Chardonnay is the most planted, and all styles from Burgundian to Full-ML Buttery versions coexist. The second most planted grape is Pinot Noir, which exhibit ripe cherry flavors and higher alcohol than burgundy. In Burgundian tradition, the vineyard is more important than the winery. The Russian River also produces some excellent Zinfandels with elegance and moderate alcohol.

The Alexander Valley is a wide valley which produces Bordeaux varietals. There is less ocean influence here, making it possible to fully ripen Cabernet. The soils are alluvial, washed down from the Mayacamus Mountains to the northeast. Cabernet Sauvignon from here tends to be softer but won’t age as long as Napa Cabs. It tends to be more velvety, and has a signature rich chocolate note. Alexander Valley also makes some rich tropical chardonnay.

The Sonoma Valley is located west of Napa and south of the other Sonoma regions listed above. It borders the San Pablo Bay, and it heavily influenced by the fog and other maritime weather. The area was settled by General Mariano Vallejo in the mid-1830’s and the town of Sonoma was founded. The first vines were planted by Agoston Harezthy in 1856, and the following year tunnels were bored into the mountain-side for ageing wine. Today there are many historic buildings scattered across the valley, as well as 100+ year old vines. The large array of varietals makes it difficult to categorize the wine style of Sonoma Valley.